A piece on writing about travel is on 'Cross Connections'

---

Shobhana Bhattacharji

The Book Review Literary Trust

VOLUME XXXII NUMBER 10 October 2008

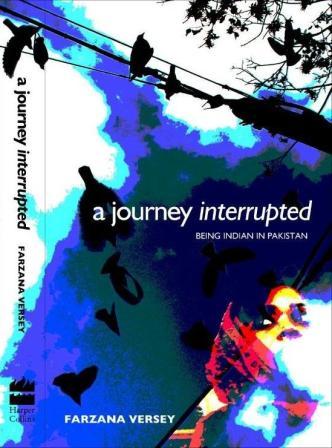

A Journey Interrupted is a secular version of nineteenth-century Indian women’s hajj narratives in which their sense of their Indian identity became stronger and stronger as their pilgrimages proceeded.1 At its simplest, A Journey Interrupted is about a Bombay-based Muslim woman journalist’s trips to Pakistan between 2001 and 2007. She visited and revisited Karachi, Islamabad, and Peshawar; she spoke to friends, politicians, army officers, socialites, poets, prostitutes, chai-wallahs, taxi-drivers, and others; she initiated conversations and had them thrust upon her; she experienced the legendary Pakistani hospitality and hostility; equally, her travelling to Pakistan was derided by friends and acquaintances in India. Summed up like this, we have another cliché, which it is not.

It is the first time I have read about feelings, ideas, and attitudes which must be part of the emotional and conversational furniture in Muslim homes but which the rest of us are not usually privileged to share. Being Muslim in India is tough enough in the normal course, with Muslims having to constantly prove their loyalty to India. It is complicated by their having close family in both countries. (This is true of other minorities like Christians as well, but that story is yet to be narrated, the dominant post-partition story being occupied by the two major affected religious groups, Hindus and Muslims.)

Versey writes as a second generation Indian affected by partition, one like me who grew up in India but among parents who knew undivided India. In the early years of this century, Asma Jehangir used to say with passion that unless our generation worked for peace between the two countries, there was no hope. Our generation, even those of us who are midnight’s children born after partition, feel we have lived in undivided India because we share our parents’ memories. But history has changed later generations.

To paraphrase Versey, they are bombarded with new weapons of hate and do not have the tolerance of the older generation who, she says, felt we should try and forget what happened and get on with life. They do not have the partial understanding but strong desire of some of our generation that we can at least cooperate and live in peace. This sounds like some more been-there-done-that.

The new thing about this book is that its rather impressionistic and sometimes dateless-diary mode is held in the strong clasp of a preface.

--

(Review updated on blog in Aug 2015)