Library, 'The Other Side'

Reviewed by Jaya Jaitly

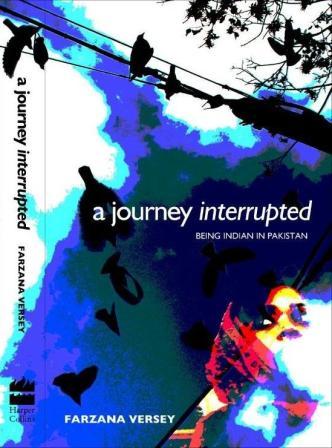

A Journey Interrupted

Being Indian in Pakistan

Farzana Versey

Harper Collins Publishers India 2008

Pages 279

Price Rs 295

Farzana Versey is a well-known, independent minded and rather spunky writer whose introverted public personality camouflages a healthy irreverence in her writings for many of the popularly acceptable norms of society. Her personal tale of many journeys to Pakistan as a proud Indian has not received the kind of publicity it is due. This is probably because she is not the wining and cheesing at a five-star hotel type. Publishers probably do not find her persona fitting the Page three book writer type either.

Despite having made a rather quiet entry onto the bookshelves at bookshops, and not being displayed in the show windows, this is one of the more genuine and perceptive books written on the layers of culture, society and history that make up Pakistan. The mannerisms of its people appear to be alien but we soon realize there are their counterparts in India. When seen through the eyes of an Indian they become instantly recognisable. At one point Farzana comments on a man she meets at a social occasion: “Fazal was a man on the make and Aijaz was a collector – a collector of contacts; he called them friends to legitimize his desperate need for networking”. The young show offs in drawing rooms and wedding entourages in so many cities of India are mirror images of these two Pakistani Punjabi men. It makes one give a further thought to Asif Zardari’s recent statement that there is a little bit of Indian in every Pakistani and a little bit of Pakistani in every Indian.

The author’s views and experiences change in nuance and understanding during her many journeys to Pakistan. They get layered like a palimpsest through which similarities and differences in textures are revealed. She probes with her curious mind the simplest of gestures and mannerisms and tells herself, more than the reader, of how it is to be an Indian visiting Pakistan. She asks, “Is there a place for secularism in an Islamic society? Or Atheism? Atheism remains the invisible minority: they have no heritage to uphold. No blasphemy laws apply to them. Non-belief is a private wound that you nurse quietly”. In a form of anwer, she shares a note she received from a Pakistani before she even went there:

When I was a child I used to think a lot about God and admired his power and grandeur. Then I thought I should find out whether this guy exists or it’s a hoax. I did it this way. I decided to talk to God, and I said “ I will call you an s.o.b. If you respond, then you exist and if you don’t then you don’t , then I am your creator and not the other way round, and if you hurt me for calling you an s.o.b., then you are an s.o.b. and not God” . Nothing happened. I therefore concluded that he did not exist or I left him with no choice but to remain silent”.

Written with a light touch, but with deep thoughtfulness, this book is one of those that stand out because the writer is both natural, sincere, and does not fear to be what she is.

- - -

Jaya Jaitly is editor of 'The Other Side', a socialist journal, and has been working for the revival of Indian crafts. She is the innovator of Dilli Haat and the former president of the Samata Party.

- - -

This review appeared in an issue in 2008, but I discovered about it only a couple of months ago!

A piece on writing about travel is on 'Cross Connections'

A piece on writing about travel is on 'Cross Connections'

---

Shobhana Bhattacharji

The Book Review Literary Trust

VOLUME XXXII NUMBER 10 October 2008

A Journey Interrupted is a secular version of nineteenth-century Indian women’s hajj narratives in which their sense of their Indian identity became stronger and stronger as their pilgrimages proceeded.1 At its simplest, A Journey Interrupted is about a Bombay-based Muslim woman journalist’s trips to Pakistan between 2001 and 2007. She visited and revisited Karachi, Islamabad, and Peshawar; she spoke to friends, politicians, army officers, socialites, poets, prostitutes, chai-wallahs, taxi-drivers, and others; she initiated conversations and had them thrust upon her; she experienced the legendary Pakistani hospitality and hostility; equally, her travelling to Pakistan was derided by friends and acquaintances in India. Summed up like this, we have another cliché, which it is not.

It is the first time I have read about feelings, ideas, and attitudes which must be part of the emotional and conversational furniture in Muslim homes but which the rest of us are not usually privileged to share. Being Muslim in India is tough enough in the normal course, with Muslims having to constantly prove their loyalty to India. It is complicated by their having close family in both countries. (This is true of other minorities like Christians as well, but that story is yet to be narrated, the dominant post-partition story being occupied by the two major affected religious groups, Hindus and Muslims.)

Versey writes as a second generation Indian affected by partition, one like me who grew up in India but among parents who knew undivided India. In the early years of this century, Asma Jehangir used to say with passion that unless our generation worked for peace between the two countries, there was no hope. Our generation, even those of us who are midnight’s children born after partition, feel we have lived in undivided India because we share our parents’ memories. But history has changed later generations.

To paraphrase Versey, they are bombarded with new weapons of hate and do not have the tolerance of the older generation who, she says, felt we should try and forget what happened and get on with life. They do not have the partial understanding but strong desire of some of our generation that we can at least cooperate and live in peace. This sounds like some more been-there-done-that.

The new thing about this book is that its rather impressionistic and sometimes dateless-diary mode is held in the strong clasp of a preface.

--

(Review updated on blog in Aug 2015)