Despite its imperfections—a jerky, disjointed narrative and long passages of recorded history—this is an interesting book, made so by the searching questions she asks her protagonists and gets asked in return.

It reads like a heated debate, on theology, diplomacy, perceptions, the Muslim identity and radicalism, democracy and dictatorship and cultural cross currents.

Versey terms the CBMs as “designer peace” and concludes that real peace will never come: being anti-Indian is a crucial component of the Pakistan identity despite their obsession with Bollywood films and Indian television soaps.

She writes with anguish and pessimism, a journey into hearts of darkness with no light at the end of that distorted prism, mainly because as she astutely observes, “every few years Pakistan writes a new fiction” to keep the embers alive.

DNA

The trouble with A Journey Interrupted is that it is a difficult book to get through, largely because of the writer’s tendency to lapse into florid description. Pakistani dancer Sheema Kirmani, for instance, enters the pages “like a story waiting to be told.” Her exit is equally dramatic: “I left her alone. Her eyes flashed embers.” This is pretty much the tone for most of the book, and while it makes for good drama, it is exhausting to read at length, and makes the characters seem less real.

Versey is much better when she leavens all that intensity with some humour, as when she describes a TV actress repeatedly muffing her one-line dialogue (‘Nahin!’). Her reflections on the complex relationship between Indian Muslims and Pakistan and the questions her travels raised about her own faith and feelings for her country are interesting and almost painfully honest.

The Mail Today

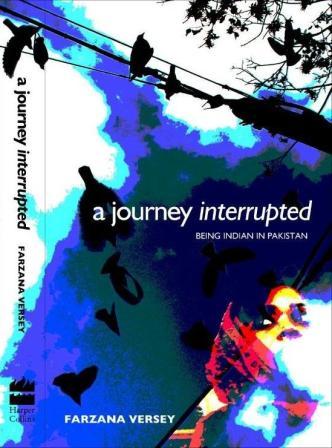

WHAT makes an Indian woman undertake four trips to Pakistan in a span of six years? No, it wasn’t with a book in mind — Farzana Versey, the author of A Journey Interrupted, Being Indian In Pakistan , clarifies that at the outset. It also wasn’t “… to find herself,” as someone at a well- heeled party in Mumbai quipped when Versey was away in Pakistan. It’s only when one grows with the book does one realise that the trips could not be summed up in a single- line answer. The visits contained too much and revealed too much, both about India and Pakistan, to be summed up as a definite answer.

As you start with Versey on her quaint trips across the Radcliffe Line, you realise that Pakistan may be just next door, but it is one of the longest distances that an Indian can travel in a lifetime. The journey, once begun, becomes yours. And as an Indian reader, you also start realising what is India — after all, it’s only when our country is juxtaposed with Pakistan that we realise what makes us ‘ us’ and them, well, ‘ them.’

Versey recounts experiences of each of her trips with vivid details and they are enmeshed with vignettes about Pakistan, both from immediate past and even remote past. So, as you read along, you realise that you are peeling off layers from the present day face of the country and gradually understanding how its past since August 14, 1947 has shaped up its present. It may be old wine in new bottle for Pakistan observers who are as old as the two neighbours of the subcontinent, or maybe even older, but for those who came in too late to be affected fatally by the events of 1947, 1965 and even 1971, it is definitely an interesting read. For instance, in two pithy pages, she sums up the transformation of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto from being the man, “… who asked Yahya to arrest Mujib ( ur- Rehman, in East Pakistan). It was a matter of time, before he became the leader.” She ends the run on the topic with Zia- ul- Haq taking charge of the country and Bhutto being sentenced to death by a Lahore court. She writes, “ As the noose went around his neck and the world stood shaken, Brutus transformed into Caesar.”