The News, Pakistan

July 6

Peshawar was the only big city in Pakistan where my religion was of no consequence

By Murtaza Shibli

After more than two decades in newspaper and magazine writing, and more than 2,000 articles to her credit, Farzana Versey still cannot be categorised as a journalist -- she makes even outside events seem like her own, as she did in her recent book, entitled A Journey Interrupted: Being Indian in Pakistan. She has written columns and features for many publications, such as The Asian Age, Illustrated Weekly of India, Times of India, Sunday Observer, Gentleman, Deccan Chronicle and CounterPunch, but then she has also taught the visually-impaired, worked among the children in red-light areas, and as she says, "these have given me a sense of loss as well as hope."

It is evident that Farzana Versey enjoys interacting with people. She has interviewed several well-known personalities from politics, arts, literature, academia and the underworld. She is currently working on the biography of former Indian Prime Minister VP Singh. Most of her articles deal with contemporary political issues of the Indian subcontinent, communalism, gender, culture, society and the media. She makes no secret of her clear-cut views on issues and sometimes her self-professed "healthy disregard for objectivity" generates a lot of heated criticism. Accordingly, she tends to bring out extremes in both fan loyalty as well as adverse criticism, including abusive feedback and threats.

To leaven the straightforwardness of her political writings, Farzana Versey pens poetry. In her own words, "Words are my weapons, they are also my shield. They are a blessing and they are a curse." Open about herself, many of Farzana Versey's writings have an autobiographical element, including her travels. The News on Sunday interviewed her recently. Excerpts follow:

The News on Sunday: You recently visited Pakistan for the fourth time in the last six years and now a book on the county. Why Pakistan?

Farzana Versey: A more appropriate question would be why not Pakistan for all these years and why now? I have spoken about the fear of visiting that country and being stuck there in the event of a war. That fear remained. In some ways, the first trip was to purge that fear; the subsequent visits were to understand the hurt of the statement I begin my Prologue with when the retired army general said, "You need to be deported." I sensed a deep resentment in his voice and tone. Moreover, it was directed not against India, but against the Indian Muslim. He was hitting out at my identity.

TNS: The subcontinent's partition is prominently placed in your discourse. Is it still that relevant?

FV: I would say the partition resonating in my book A Journey Interrupted: Being Indian in Pakistan is more psychological. I have compared the attitude of the pre-partition generation, which has now taken on a soft-focus, let us forget it all and get over it attitude, with that of our generation and, more importantly, the younger generation. We are, as I wrote, living contemporary history. The youth is finding absolutely no connection with us. The geographical partition, however gruesome it was, at least had the advantage of bloodshed. The suspicion the Indian Muslim faces both at home and in Pakistan is without this benefit of catharsis. The fissures are only being fossilised with every stereotype.

TNS: Can the ongoing peace process between the two countries heal the wounds?

FV: As I have already said, we are not talking about those old wounds as much as about the new arrows being aimed blindly from both sides. Political peace is impossible and will never happen. I am afraid if this is a pessimistic view. I would call it freedom from delusion. It would suffice if the ordinary people kept up a semblance of civility and left politicians out of the peace process. When you want to sup with your neighbour you do not seek the permission of the landlord, do you?

TNS: Was it possible to do a book without Kashmir in it?

FV: I tried, but Kashmir was like a shadow tailing me. The reason is simple: the Pakistani interest in India is centred on Kashmir. Not the Kashmiri people, mind you, but Kashmir as real estate, as a brownie point. And this will continue to be a hotbed, because the most important thing is that this one state keeps the armies of both countries occupied. It has probably become a symbol to judge how patriotic one is.

TNS: Why did you choose Indian Muslim identity to set the narrative?

FV: Because it happens to be my identity. And this book is about the identity question in large measure -- my identity, the Pakistani identities. You forgot to add the 'woman' identity too. This was crucial because a female perspective put me in the real conflict with the terrain. Given that Pakistani society is considered misogynistic, I got to see it in action in my encounters with men from different strata. I do not think a man would ever write about Peshawar the way it has been written and I do believe I have shown the women of the Frontier as I saw them without wearing blinkers. If I saw an amazingly courageous rebel in a village here, I saw the complete helplessness of the so-called liberated woman in a big city too. There cannot be fixed ideas. Incidentally, Peshawar was the only big city in Pakistan where my religion was of no consequence.

TNS: Despite placing your Muslim identity at core, why are you seen as an infidel?

FV: This must be seen in the context of my various fractured selves that came along as baggage. I do tend to travel heavy! I referred to feeling like an emotional mulatto in the land of the pure where my supposed impurity hit me. This personal aspect was to take off on other marginals.

TNS: You are using a limited set of people to comment on the society. How exhaustive can this be?

FV: I am not a bird, so there was no sense in giving a bird's eye-view. I had not set out to write the definitive book on the Pakistani society, with a title that had every word in caps and footnotes that ran into pages. Interestingly, while researching some aspects it would take me to many of my earlier articles, so a bibliography would have ended up as an exercise in vanity that I can ill-afford beyond a point.

To answer your question, it may not be exhaustive, which is why it is not exhausting. However, it is most certainly relevant because those people are an intrinsic part of the country; they are its voices. Mores and norms are formed by lived experiences, not pontification.

A Bengali Muslim talking about Bangladesh makes more sense to me than my quoting ten experts. That information is available from any search engine. And will anyone be able to replicate the sheer anguish of people's personal lives by not empathising with it? I could have written a nice sensational chapter on Heera Mandi, but as I stated I am not a western sociologist 'doing' a place; my sensitivity is different; not better or worse, just different. I have a background in working among children of commercial sex workers, so I cannot take those images away. What I have instead is a more touching account about a real person who is hiding her past. We again come to the identity question. What is hidden is often more potent.

TNS: How would you compare Indian and Pakistan identities?

FV: I called Pakistan an amputated nation; some would see it as trashing. I see it with anguish. Therefore Pakistan, as I believe and several people there do, is restructuring its identity to deny its roots. This is a tough call. The Indian identity is about the memory of what has been taken away. India does act like Big Brother, but it is surprisingly insecure about the loss. The constant sloganeering about 'India Shining' is really an attempt to gloss over that.

TNS: The current struggle for democracy in Pakistan is generally seen as an intellectual one. Do intellectuals and civil society feel trapped in the milieu that has shaped the country?

FV: The intellectuals are not of one stripe, as they ought not to be, so there are differing versions of democracy. An Ahmed Faraz has a vastly different take from a Sheema Kirmani. Faraz is attached to his passport, Sheema does not even believe in the concept of nationalism. The section on dissenters was mainly to question them about the Pakistani identity and many felt there was none. I would like to add here that it is easy to term liberals dissenters, but I have included the Jamia Hafsa women because in many ways they set the tone of the current crisis of rebelling against the system. I find this most interesting because in an Islamic society you have bunch of Muslims, women at that, going around with sticks. We really need to broaden our way of looking at the idea of dissent.

TNS: What kind of India lives in the public memory of Pakistan?

FV: The India they can still conquer! Besides Indian films and soaps, Pakistanis think India is a Hindu nation. Perhaps they are trying to justify their Islamic nation call. This was my major grouse as an Indian Muslim.

TNS: Your interaction with gays and minorities is interesting. How do they cope in the supposedly harsh Islamist settings?

FV: The gays are doing fine as long as they stick to their groups. Let us not forget that homosexuality is illegal in India; in Pakistan, there is no such law. It is against sodomy. So you can feel up a guy and no law can do a thing, unless someone is there to watch you in the act. The more touching aspect is about gay women, and they do exist. Religious minorities have their own problems, but they have found canny ways to deal with it. Say 'Allah Hafiz' and all is well with the world.

TNS: Your book is wanting for any interactions with Islamists. Why didn't you try to meet any?

FV: If by Islamist you mean the totems that have made it their vocation, then no, I did not attempt to meet any. The very idea about debunking stereotypes is to first understand them. My understanding is being an Islamist is not a profession. Therefore, if you look carefully there are traces of all the types you mentioned. I cannot identify some for obvious reasons. For me the genesis is more important, and I found it in the person who joined the Tablighi movement or the atheist who completely changed. What prompts those changes? That leaves more room for exploration.

TNS: Is there any difference in pre- and post-9/11 Pakistan?

FV: If there is anything that should tell Pakistan that it is not an Arab country, it is this. Before 9/11, the bookshop owner in Peshawar was not enthusiastic about selling Osama's biography to me. Post-9/11, Osama was lionised with posters everywhere. And in 2007, when I last visited Pakistan, his posters were peeling and no one cared for him. But anti-Americanism is perhaps more prominent as indeed are American accents. A society full of contradictions...

TNS: As Indian Muslim, how different did you feel from the cousins of your extended family in Pakistan?

FV: Completely different. Mainly because unlike the pre-1947 elders, like my mother here and aunt there, we do not share any memories. And memories make all the difference.

* * *

BOOK REVIEW

Story of an "emotional mulatto"

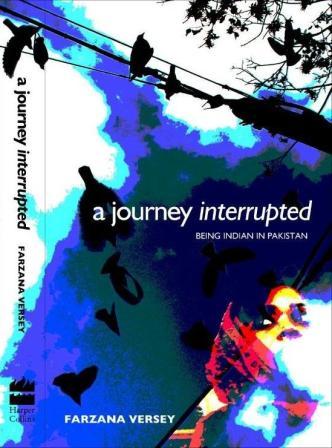

A Journey Interrupted: Being Indian in Pakistan

Author: Farzana Versey

Publisher: Harper Collins India

Price: 295 Indian rupees

Pages 279

Being a Muslim in India is a tough job. Threatened and terrorised by a growing number of Hindu militant extremists, and constantly looked at with suspicion and treated with a certain degree of caution, the Muslims are believed to harbour a certain desire to separate from the union and create a country of their own a la Pakistan, which a modernist Jinnah created but has since been usurped by the dubious Islamist agenda. The suspicion is so institutionalised that the Muslims are hardly represented in the country's million-plus armed forces.

This suspicion turns into contempt when an Indian Muslim travels to Pakistan. In the popular Pakistani imagination, India is a country of Hindus and if at all there are any Muslims, they are seen as infidels. Farzana Versey's encounters in Pakistan are replete with her confrontations with such stereotypes. However, as her expedition of exploration furthers, she finds fascinating contours of a human society with diametric contradictions where 'personal becomes political'. Reading her account in the book under review it seems that the Indian Muslims face more suspicion in Pakistan, because they are not treated on par with the Indian Hindus in the country that is supposedly Muslim.

In A Journey Interrupted: Being Indian in Pakistan, Farzana Versey weaves a collage of her experiences that she acquired during her four visits to Pakistan in six years -- a journey of exploration with continuous negotiations and constant reconciliation with her own identity of an Indian Muslim woman. "When I was on the soil of the land of the pure, my impurity struck me. I was the emotional mulatto," she writes. She travels through the cities of Karachi, Islamabad, Lahore and Peshawar and meets a vast array of people -- common tea-sellers, prostitutes, actors, poets and retired army men -- to find out strange and contrasting factors of the Pakistani identity, if at all there is one.

Despite dancing to the tunes of Bollywood films and replacing the peeling posters of bin Laden with the likes of Shah Rukh Khan, being anti-Indian is an important part of the Pakistani identity. Kashmir fits perfectly in that quest for a national narrative that has been interrupted by army dictatorships, political mismanagement and Islamist Jihadism. In order to sustain the rationale of a struggling identity, Farzana Versey writes, "every few years Pakistan writes a new fiction". The book is "about Pakistan, but it is also about India. It is about Them and Us, Her/Him and Me," she contends.

Though not a 'conventional' travelogue, A Journey Interrupted: Being Indian in Pakistan could not escape the trap of Kashmir -- the place that defines the 'convention' between India and Pakistan. "Kashmir was like a shadow tailing me," the author told this scribe. The reason is simple, she adds, "the Pakistani interest in India is centred on Kashmir. Not the Kashmiri people, mind you, but Kashmir as real estate, as a brownie point. And this will continue to be a hotbed, because the most important thing is that this one state keeps the armies of both countries occupied."

Farzana Versey terms the ongoing peace process "designer process", observing that "political peace is impossible and will never happen." She describes her observation as "freedom from delusion", but adds, "it would suffice if the ordinary people kept up a semblance of civility and left politicians out of the peace process. When you want to sup with your neighbour you do not seek the permission of the landlord, do you?" The book under review is written primarily from an Indian Muslim perspective, which subtly tries to debunk a few stereotypes that exist about both Pakistanis and the Indian Muslim 'affiliation', a cause to which both the Hindu militants in India and the Islamist extremists in Pakistan are wedded.

As India and Pakistan are trying to overcome the legacy of Partition and build new bridges, Farzana Versey -- while watching from the Pakistani side of border at Wagah -- feels unsettled by the "unsheathed anger and the charade of candle-lit peace", and finds proximity and not the distance "disturbing". A wonderfully written account, the author uses terse language in effective idiom, imagery and poetic observation. In these times of political and social unrest in Pakistan, this is a timely book -- one that delves into the Pakistani mind and traces the chasms in its recent history.

- Murtaza Shibli